| |

and

then what? (and then what?)

by Robert Cook

A few years ago Paul Hinchliffe and I sat in a Leederville coffee

shop talking about the weather. It was raining. We were clear about

that. Which was good, because I was far from clear about a definition

of Paul's "art practice". That's what we were really there

to discuss, for a newspaper article I was trying to write. Paul

told me he'd made sculptures on the beach at Quinns Rock. That he

left them there. Didn't even take photos. Maybe people stumbled

upon them. Maybe they were puzzled. Maybe they weren't. He told

me how he sat down with the international atlas, found a street

name and sent a package off to an unknown addressee. It was a gift.

He talked about the Hiematlos (homeless) project. Performances in

carparks. Subterfuge in art galleries. Conceptualism and hobo-ism

uniting. Just like Jack Kerouac and Richard Long said it would.

We shook hands and I ran to my car. I got soaked to the skin. I

shivered, went over my notes in the office. The rain got harder

as I typed them out, drowning out my keyboard plucking. My editor

didn't like the result. There was no hook. He'd as soon can the

story, if I didn't mind. And I didn't. Not really. For me, the interview

was just another chance to piece together a puzzle I'd been trying

to figure out for a decade or so, since experiencing Paul as a lecturer

at art school.

To me, dopey and callow to the marrow, Paul was the unexpected incarnate.

I'd arrived there, you know, just wanting to make stuff. Paul never

made stuff. Or the stuff he made was more like anti-stuff - blank

books, verbal images of Pythagorean formulae. Paul was the guy we

first heard about Lacan and Derrida from. But, unlike so many of

us who later delighted in what riot grrrl band Le Tigre call

Fake French [1], he wasn't name-dropping. And he wasn't "applying

theory" either. He was inside it, tied up and twisted. To be

honest, it was kinda painful to see. Yet, from remote Lacanian lacunae

he made us ask ourselves what we were looking to art school for.

He made us realise that art is fundamentally about the transference.

Art is about the questions we ask of it, the responses we want back

from it. So, when identity politics were all the rage, when lines

were being drawn in the sand, Paul was ontological man. Yes, it

was unsettling. He frustrated us enough to make us think for ourselves.

At the same time he teased us. Thinking for ourselves, properly,

was a discursive impossibility. With Paul there were no platitudes

to settle upon.

So you'll forgive me if I admit I'm suspicious of his new work.

Work in a gallery no less. Work that seems sumptuous, even. I don't

trust my reaction, my pleasure. Mostly I don't trust him. I've been

burnt enough times to know that any claim to sensory pleasure is

deeply rooted in a critique of such phenomena.

Okay, critique is the wrong word. Utopia doesn't await. Desire rules

that out. Like Ramsay Street, art is a cul de sac to which we return

again and again searching for something, finding that content, context,

perception, and plain old longing are bound into the one infuriatingly

dumb object - a thing on the wall. Or Harold Bishop.

So, sure, Paul is putting things on the wall these days. And then

what?

We can puzzle them out, but will they have stopped functioning,

will we be complete when we're done sleuthing? This mirrors Yeats

queries in his poem "What Then?":

The work is done, grown old he thought,

According to my boyish plan;

Let the fools rage, I swerved in naught,

Something to perfection brought;

But louder sang the ghost, "What then?" [2]

Despite our best intentions, nothing will be resolved. The work,

(all work), remains fugitive, a series of offerings, openings and

refusals, doors slammed in the face, heads turned abruptly.

Like Lacan, Paul refuses to play the good daddy, to be our friend,

to console. I find no comfort in this.

And yet, I'm invigorated. Though I want the work to love me back,

to let me love it, there's something tragically beautiful about

the dilemma. The new work toys with this, makes us think it will,

maybe, in the future, when the time is right and the moon is high.

It's something old Gatsby would understand, and my guess is Paul

and Jay would have been soul mates, knowing that everything is out

of reach, even themselves, even as they dream it otherwise.

This too is a projection. Narrative, poetry, all that. Another self-made

consolation.

It's annoying. Paul reminds me how much I need these things, how

weak I am.

Again, I find no comfort in this. And can find no graceful way to

exit this text.

There is always another "what then?"

And maybe I still don't really get it anyway.

It's raining today. Did I mention that?

Notes

[1] Le Tigre. (2001). "Fake French", on Feminist

Sweepstakes, Tilt Records: Sydney. They sing: "I've got - the

new sincerity. I've got - a secret vocabulary. I've got - dialectical

sprecstime. I've got - a conceptual stunt double. I've got - site

specificity. I've got - flow disruption. I've got - wildlife metaphors.

I've got - post-binary gender chores....My Fake French is hot. You

can't make me stop".

[2] W.B. Yeats. "What Then?", in Seamus Heaney, (2002).

Finder's Keepers: selected prose, 1971-2001. faber and faber:

London. p.109.

*prices

valid 2003

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

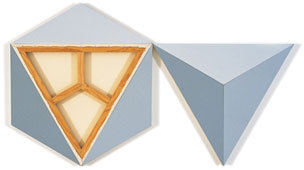

no

answer

acrylic, canvas, pine

181 x 181cm

2003

$6600

|

...

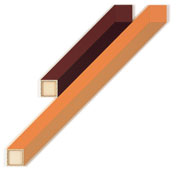

to catch a herring #2

acrylic, calico, tasmanian oak

140 x 140cm

2003

$1650

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

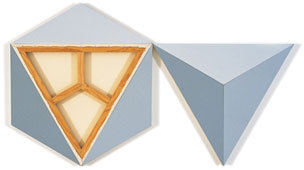

a

round mirror

acrylic, canvas, pine

104 x 90 + 78 x 90cm

2002

$3200 |

...

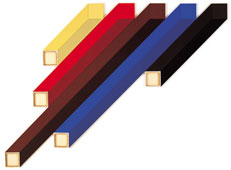

to catch a herring #3

acrylic, calico, tasmanian oak

160 x 190cm

2003

$2400

|

|

|

|

|

|

the

last leaf

acrylic, canvas, pine

203 x 126cm

2003

$6000

|

...

to catch a herring #4

acrylic, calico, tasmanian oak

160 x 190cm

2003

$3100

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

blue

paper

acrylic

/ canvas / pine

95 x 132cm

2002

$2300

|

...

to catch a herring #5

acrylic, calico, tasmanian oak

160 x 220cm

2003

$4100 SOLD

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

the

white owl

acrylic, masonite, pine

31 x 21.5cm

2003

$770 SOLD |

a

large window

acrylic, canvas, pine

158 x 132cm

2002

$4700

|

|

|

|

|

|

the

loving calm

acrylic, canvas, pine

41 x 203cm

2003

$1650 SOLD |

|

|

|